Regular

Medium

Bold

Jungmyung Lee

Basic Western European

Central European

South Eastern European

between Karel Martens and Jungmyung Lee.

It derives from the most widely used fonts;

Akzidenz Grotesk,

Helvetica and Univers.

We wanted to make a grotesk font

positioned somewhere between

Akzidenz grotesk, Helvetica and Univers

- not as dry and distant as Univers,

but devoid of the quirky uniformity of Helvetica. Jungka is more reminiscent of Akzidenz grotesk than the other two typefaces. Like Akzidenz grotesk its letterforms are autonomous in width and have a contemporary feel in their curves and straight lines. Yet Junka’s accentuated circular curves evoke a soft, friendly, and rhythmical atmosphere.

Jungka shares the quality of a classically crafted sans serif typeface by taking its formal cues from these historic predecessors. However, fine-tuning its space for text enhances legibility with a modern touch.

Written by Laura Pappa

Jungka Book Italic

Jungka Regular Italic

Jungka Medium Italic

Jungka Bold Italic

Skywriting message captured by Digital Globes GeoEye-1 satellite just South of Orlando Florida.

The last letter of the word on the left side was cut off by the orbit path, but the remain three clearly spell GOL …

GOLF?

GOLD?

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

What could be more refreshing than a long walk on a sunny afternoon, enjoying a wide open sky with a few chance cloud puffs sailing by? When stopping for a while to gaze at the grand calm, a passing cloud could reveal a familiar face. A flock of birds might be seen making their routine journey across the sky or, if caught at the right time of year, you could even witness a great swathe making their annual migration, a massive V-shaped army. And if your walk was to take place at dusk, you will slowly be welcomed by constellations of stars, whose changing alignments never cease to surprise.

Yet there is more that wanders the sky than just clouds, birds and stars. A large, metal creation roams around in huge numbers: the airplane. This new species has brought about a number of new signs and signals that tend to crop when you least expect it. Some of these have come to be called “skywriting”.

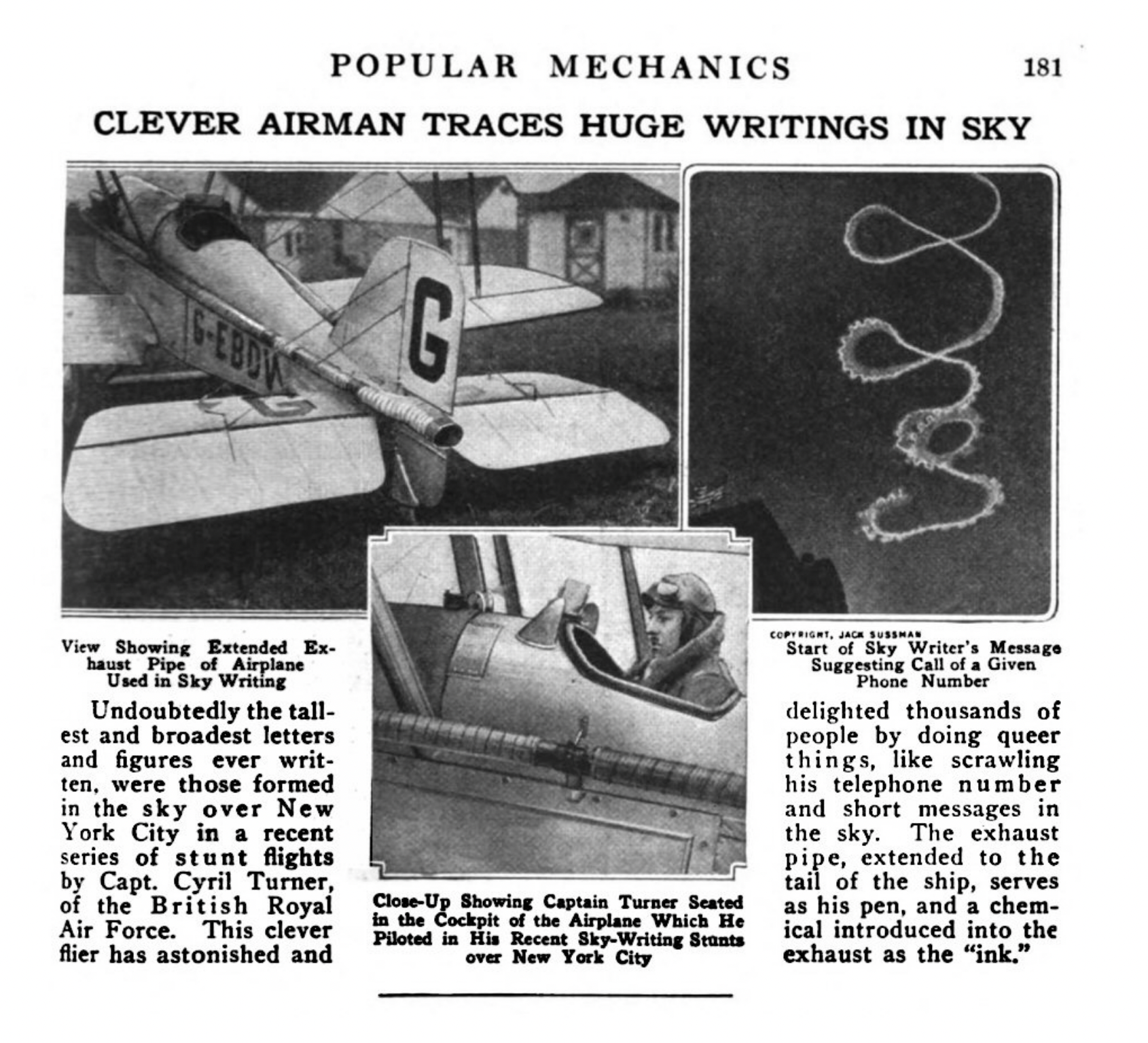

Popular Mechanics magazine covering the arrival of skywriting in America in February, 1923

.

.

THE RISE OF SKYWRITING

.

Now already a largely distinct format, skywriting emerged between 1910 and 1920 in England. Its invention is attributed to Major Jack Savage, a former British Royal Air Force pilot and writer for Flight magazine*. The technique involves using a small aircraft to transfer messages across the sky by means of expelling smoke during flight. With sky writers required to write upside down and backwards, it is by no means the easiest of jobs:

*

Although most sources attribute the invention of skywriting to Major Jack Savage, others claim that it was in fact Art Smith, a celebrated American stunt pilot notable for flying at night. Smith is said to have finished his night time shows by using flares attached to the aircraft to sign off with ‘GOOD NIGHT.’ laid out in calligraphic smoke letters.

As with any form of art, having the right tools will only get you so far. What really matters is pilot talent. The skywriting (or skyart, really) is done by a skilled pilot who is able to maneuver the aircraft in such a way to form the letters so they are visible from the ground—while knowing when smoke is needed to make the letters. It requires extremely precise flying and the ability to factor in everything from the position of the sun, the position of the crowd, the direction of the wind… It’s certainly not the easiest job in the world, which is one of the reasons not many people do it anymore.

.

.

.

_

(` ) ▪

( ) ▪

_( ‘ ` ▪ _ _

▪ =( ` ( ▪ ) ▪

( ( (▪ ▪__ ▪ : ‘—’ ▪ +( )

`( ) ) ( ▪ )

` __ ▪: ‘ ) ( ( ) )

__’ ` — __ ▪ ‘

As with any potential message conveyor, it was soon picked up by the advertising industry. In 1922, another ex-RAF pilot, Cyril Turner, used Savage’s techniques to write ‘DAILY MAIL’ in the skies over Epsom Downs in England.

A bumper crowd for one of the biggest racing weekends of the year was enthralled as the silver speck 10,000 feet above them spelt out DAILY MAIL in vast white letters which, the newspaper later claimed, was ‘the greatest single development in outdoor advertising’ and that ‘everyone within an area of a hundred square miles – and there were millions – gazed spellbound at this fascinating sight.

In the same year, Turner and Savage also brought the format to America, writing ‘HELLO USA’ in the sky above the Times Square in New York, only to appear again the next day to finish off what he had started ‘CALL VANDERBILT 7200’.

The ad men on Madison Avenue were astounded by the public’s reaction. VANDERBILT 7200 was the phone number of the hotel at which George Hill was staying, and in the next three hours the hotel switchboard lit up non-stop as eight operators fielded 47,000 telephone calls.

This kicked off the rise of a new business in America. Companies tired of the traditional print and radio commercials enthusiastically turned to skywriting as a fresh and powerful new tool to draw attention to whichever product or service they were providing. In 1923, the American Tobacco Company created the first ever successful advertising campaign for Lucky Strike by painting the skies with ‘L S M F T’ (Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco) over and over again. Needless to say, this exciting new format was very warmly received by the public. Whoever caught a glimpse of a skywriter plane in the middle of one of its printing sprees stopped to stare, awestruck at the miracle before them.

_

(` ) ▪

( ) ▪

_( ‘ ` ▪ _ _

▪ =( ` ( ▪ ) ▪

( ( (▪ ▪__ ▪ : ‘—’ ▪ +( )

`( ) ) ( ▪ )

` __ ▪: ‘ ) ( ( ) )

__’ ` — __ ▪ ‘

PEPSI COLA IN THE SKY

One of the first corporations to make wider use of this new advertising method was the (at the time little known) beverage company Pepsi Cola. In 1931, Pepsi bought their first skywriter plane and named it the Pepsi Skywriter. To fly it, they hired pilot Andy Stinis, who ended up flying for Pepsi until 1952. Having previously relied almost exclusively on radio ads, this untouched majestic surface, the sky, proved to be incredibly successful as a billboard for messages. Pepsi soon grew their skywriting fleet to 14 planes.

The rise of television in the 50s and 60s largely put an end to skywriting as a premier advertising medium. Yet after a long break, in 1973 Pepsi decided to bring back one of its legendary Pepsi Skywriter planes. It soon become the company’s mascot for the next 30 years to come.

Over the years, Pepsi has had a handful of skywriters working for them. Among them are “Smilin’ Jack” Strayer and his prodigy Suzanne Asbury, the latter of whom is one of only two female professional skywriters ever, and the only one still practicing. Their first pilot and head of the skywriting team Stinis is considered one of the pioneers of this highly demanding niche practice. In 1946, he developed a faster and less complicated skywriting technique

that he called skytyping. This method uses multiple aircrafts flying parallel and by doing so allows for the creation of more complicated images and messages. Compared to skywriting it also creates more uniform letterforms, typing in the skyline like a dot matrix printer.

But Pepsi hasn’t limited its interventions in the sky to skywriting alone. In addition to a number of custom-shaped hot air balloons, in 1996, to advertise their new brand style, Pepsi Cola decided to involve the Concorde in a special undertaking. The plan was to cover the body of a Concorde in the new Pepsi scheme, with a solid blue body and red and white tail and then take it around for a number of promotional flights. The whole operation was to be carried out in secret in order to reveal the new Pepsi Blue identity on the day of the flight. Concorde F-BTSD took off from Paris on March 31 to arrive on London Gatwick for the special launch event.

The show took place on 02 April 1996, with the presence of Claudia Schiffer, Andre Agassi, Cindy Crawford, and hundreds of journalists invited by Pepsi for the event. People were really astonished to see the Concorde with the blue livery. Flight attendants each had a special pin on their uniform designed for the occasion.

The grand show was followed by a series of promotional flights to Europe and the Middle East.

POPULAR

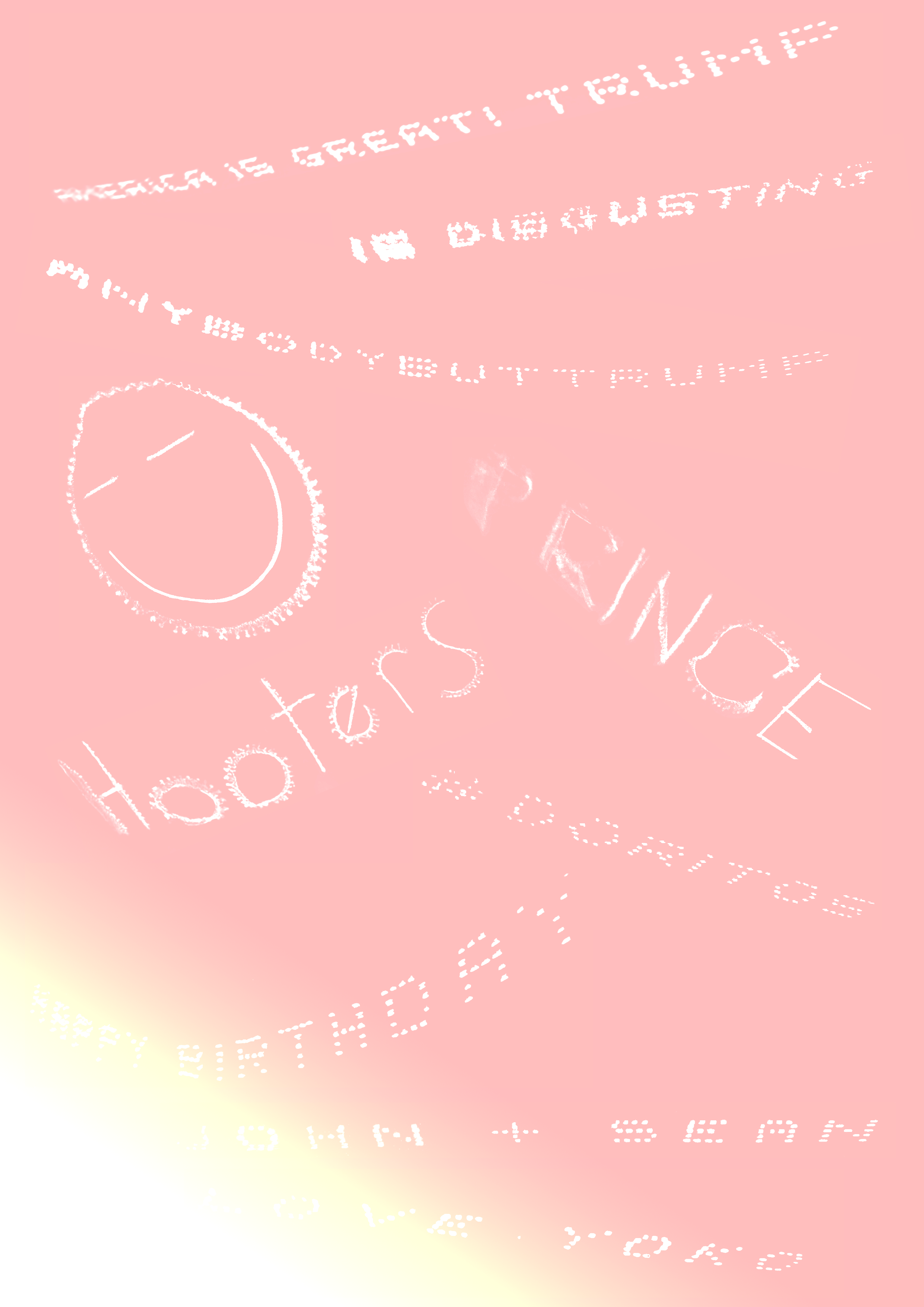

Skywriting has become popular as a way of sharing messages of all kinds. Marriage proposals, birthday wishes and seemingly random words or sentences are among the most common messages shared through skywriting. Unfortunately, due to incredibly high prices, skywriting has remained a luxury for a select few. Skies have also carried a number of political statements over the years, especially during elections.

Skywriting has often appeared in the sky during fairs, air shows and other celebratory events. On New Year’s Day of 2016 at Pasadena’s annual Rose Parade the festivities were slowly coming to a close when a number of skywriter planes emerged to share some final words. The aircraft spelled out a handful of short-lived messages all targeted at the then Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, including ‘AMERICA IS GREAT! TRUMP IS DISGUSTING’, ‘TRUMP LOVES TO HATE ‘, ‘ANYBODY BUT TRUMP’, ‘TRUMP IS A F ASCIST DICTATOR’, ‘IOWANS DUMP TRUMP’ and ‘TRUMP IS DELUSIONAL’.

Needless to say, such an overwhelming undertaking wasn’t likely to have come from just any concerned citizen. It was later revealed that the man behind this verbal assault was Alabama millionaire real estate developer Stan Pate, coincidentally a donor to Florida Sen. Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign. Pate has had messages of a similar vein appear in the sky before, mainly in the form of skywriting’s close yet less-appealing cousin: banner ads.

AMONG

On his final night before becoming president, Donald Trump had his own go at conquering the skies. After the inaugural concert at the Lincoln Memorial, the skies over Washington DC lit up with breathtaking fireworks, first displaying the American flag, followed by the letters ‘U S A’. But heads were turning not only for the majesty of the act but also because the letter A turned out to look surprisingly like an R – “United States of Russia”? The stage was set for the rumour that Moscow had hacked the inaugural fireworks.

There’s rumours that in 1970 John Lennon and Yoko Ono also made a contribution to creating some excitement in the skyfront by writing ‘WAR IS OVER IF YOU WANT IT, HAPPY X-MAS FROM JOHN & YOKO’ over the skies of Toronto. Yet in response to an article on skywriting on mentalfloss.com, a comment from somebody going by the name of Laura Salovitch expresses doubt whether this actually ever happened:

[…] I question the statement that Lennon had his “War is over if you want it…” slogan skywritten. It’s common knowledge that he and Yoko purchased a New York City billboard with that phrase, but if they hired skywriters, it would have been documented somewhere. Just sayin.

FOLKS

Other sources state Yoko had ordered ‘HAPPY BIRTHDAY JOHN + SEAN, LOVE YOKO’ to be typed several times in the sky in 1980 to mark the birthday of John and their son Sean. And indeed, besides receiving a lot of attention at the time both on the streets as well as in the media (apparently, John himself didn’t even see it), there is also photographic documentation available.

Be that as it may, it’s clear that a vital component in the success of skywriting lies in its temporality and oftentimes also anonymity. It’s a message that appears out of the blue and exists for a short instant only to vanish moments later: who saw it, saw it, and who didn’t might likely hear about this mysterious articulation from an excited neighbour or colleague the day after.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

RADAR MESSAGES

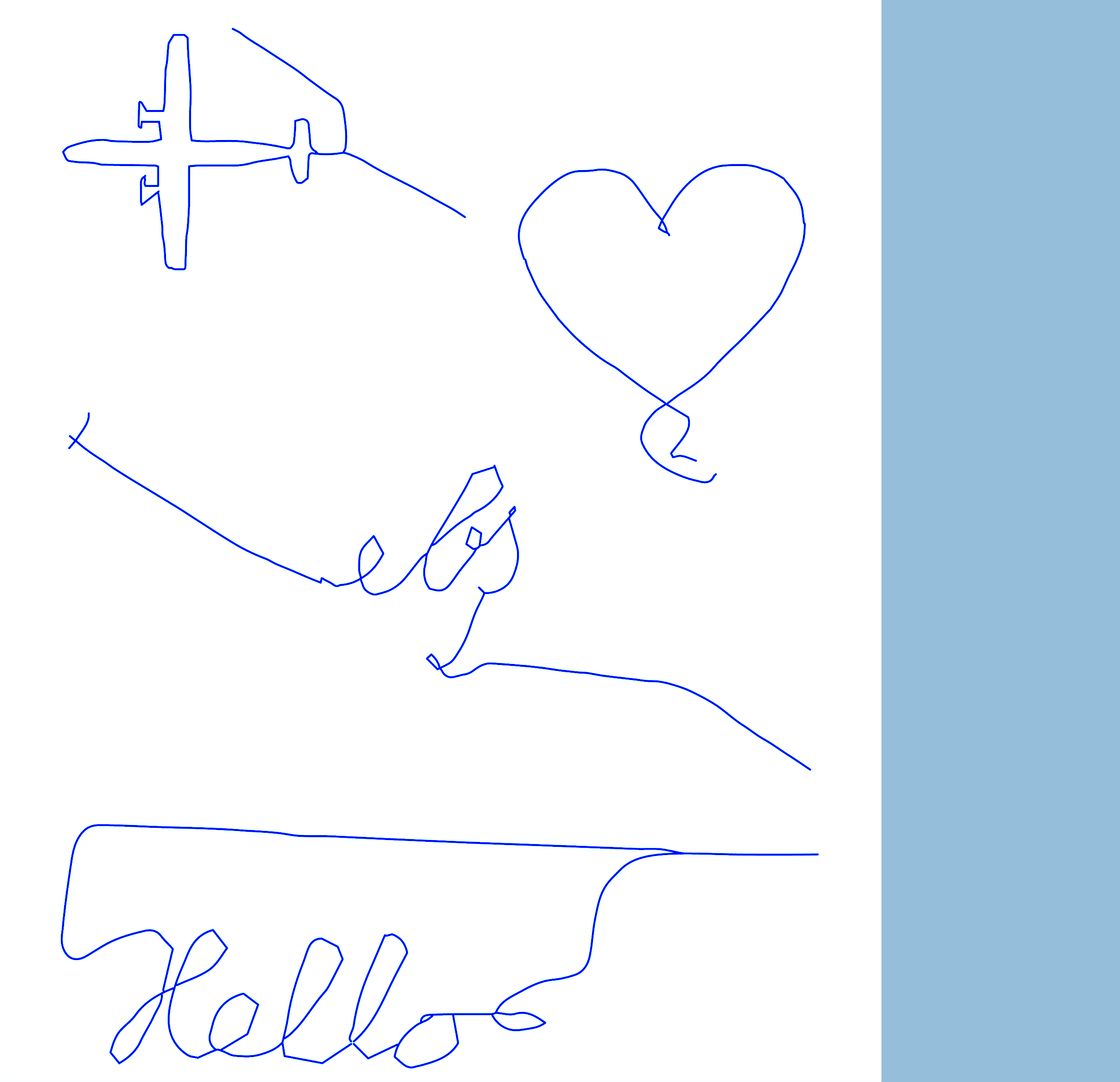

Some pilots, perhaps in dire need of a reason to become air-bound, have found a new pastime in spelling out messages via their trajectories in the sky, revealed to the public exclusively via the flight radar. This is yet another highly-demanding task – the pilot needs to plan the whole route step by step in order to complete the desired image.

The Guardian recently reported an aircraft that wrote *Hello* in the skies of Germany, calling the act one in a series of many attempts to create ‘inventive flight art’:

Flightradar24 recorded the 37- minute flight beginning near Agathenburg, in the Niedersachsen region of Germany, on Monday afternoon.

The Robin DR400/180 Régent aircraft is registered D-EFHN and is privately owned, though the identity of its pilot is not known.

Flightradar24 confirmed to the Guardian that the simulation showed a real flight, adding: “This aircraft has a history of inventive flight art.”

Earlier this year, it drew a portrait of an airplane, signing off with what appeared to be a signature; and, on a separate flight over northwest Germany, a heart.

Who was he possibly trying to address? The mystery around the work of the Robin DR400/180 Régent aircraft and its pilot remains to be solved.

According to the Guardian, such operations have been practised before, by somebody labelled ‘Flower Guy’, who draws different patterns that resemble flowers, as well as the pilot of an Air Malta flight last year who drew two hearts in the sky to mark the marriage of two of the company’s employees.

Illustrations of the routes the unknown pilot of a Robin DR400/180 Régent aircraft,

according to Flightradar24, has embarked on.

BIG

Messages appearing in the sky can elicit excitement from people of all ages: gazing up at the sky in anticipation, each newly crafted letter adding a new piece to the puzzle, what will be the whole?

While skywritten messages can come across as harmless or even amusing, knowing that only the rich can really make use of this very powerful tool is a somewhat frightening thought.

Already during the early days of skywriting, the question was put forth whether such an invasion of space should be regulated:

. . . legislation was several times proposed (and Parliamentary hearings actually conducted) to address what was thought by some to be the unacceptably unregulated and fundamentally unaesthetic clouding of the heavens by advertisements for insurance, cigarettes, soda, and patent medicines*.

*

Burnett, D. Graham. Notes Toward a History of Skywriting.

Cabinet #60, Winter, 2015–2016, p. 30

BROTHER

Sure, skywriting is slowly disappearing, but the sky remains an appealing advertising platform. At present, this is mainly practised through banner ads, airplane exteriors or vessels such as the Goodyear blimp*. But it’s hard to believe the advertising industry won’t soon expand to the skies with new technologies.

There is still something very private about the sky when compared to the majority of public space, which is increasingly veiled with a layer of commercial output. However, the prospect of something like George Orwell’s Big Brother staring back at you from up above doesn’t seem like such a distant future. And it’s perhaps only a small relief that a community exists which is on constant lookout to discover and reveal concealed messages in the sky (see the commotion created around the so-called “chemtrails”**). Indeed, already witnessing occasional political sky messages can give a glimpse into a world where the sky is constantly invaded by this kind of messaging. What if the skywriting never stopped?

*

The Goodyear Blimp is any one of a fleet of airships operated by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, used mainly for advertising and capturing aerial views of live sporting events on television. The term blimp itself is defined as a non-rigid airship. The Blimps help the company advertise its products and also deliver public service messages from various organisations such as local governments.

**

There’s a well-known conspiracy theory that associates long-lasting contrails, labelled chemtrails, with the government spraying chemical or biological agents to the sky for purposes such as solar radiation management and weather management. The scientific community has dismissed such allegations saying that the long-lasting visible trails are left behind under certain atmospheric conditions.